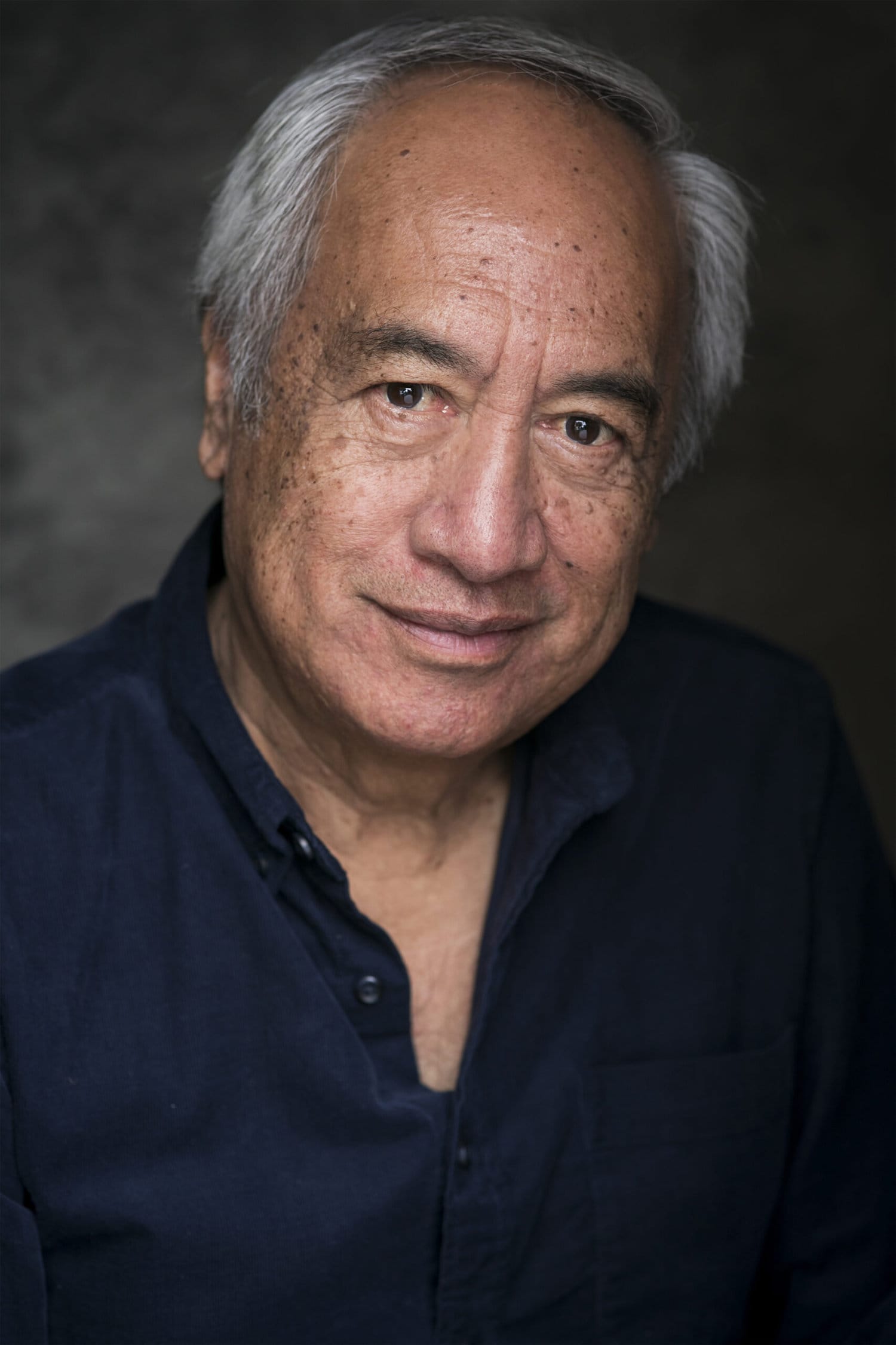

Fifty years ago this year, Witi Ihimaera published his debut novel, Tangi, the first novel by a Māori author. Tom McKinlay caught up with the celebrated writer on the eve of his visit to Dunedin for the city’s Readers & Writers Festival.

Words Tom McKinlay | Photo Andi Crown

In Tangi, the protagonist and eldest son Tama is called back to the whenua (land), to the family farm when his father dies. To tell the story, Witi Ihimaera employs his trademark spiralling narratives to collapse time and recall the close relationship between father and son, contrast the competing claims of the papa kāinga (ancestral land) and the outside world, and convey the heartbreakingly sad yet life-affirming traditions of the tangihanga (funeral rites).

It’s 50 years this year since your first novel, Tangi, the first novel by a Māori author, was published, how does the significance of that event strike you now?

I wrote Tangi while on honeymoon at 67 Harcourt Terrace, London, just off the Old Brompton Road. I also completed Pounamu, Pounamu and Whanau there in the same year, 1970 – they should put a plaque on that building.

So Tangi is very much a London novel. And the location and my interest in postcolonial literature gave me an interesting perspective on writing it. I thought it was time for a Māori to join African, Caribbean, Indian and Black American writers in shaking that Eurocentric tree and, well, the whakapapa (genealogy) of the Māori novel written in English had to start somewhere and at some time and 1970 was, in my opinion, already rather late in New Zealand.

Tangi was the first of the short stories from Pounamu, Pounamu developed into a novel. But it wasn’t the only story in the collection – which you have described as your Rosetta Stone – to provide a stepping off point for a novel, the beginnings of The Whale Rider and Bulibasha can also be found there. Why did you choose Tangi to begin with?

I’m glad you’re connecting Tangi with Pounamu, Pounamu (and we should add Whanau into the mix) because they form my Waituhi trilogy and, being written within the same timeframe, are pretty much one book.

Having said that, yes, Pounamu, Pounamu was my template, my green-print and, even while writing the short story, my senses became attuned to the way it was playing with time and telling a captivating story of a young Māori boy’s love for his dad. That, really, is what the novel Tangi is about.

The rest of the novel grew around that story when I decided to frame it inside the three-day tangihanga, which I thought was imperative if the novel was to be tūturu Māori, centred within a Māori rather than Pākehā world.

It remains an intensely emotional read – was it especially demanding to write given the subject matter?

The demanding part was writing about dad as if he were kua mate (passed away). In 1970 he was 55 and mum told me that if I was really going to be a writer (she was really against it, but that’s another story) I had to complete Tangi before he died, otherwise the people back home would think it was about him, ie, real. That’s why I wrote it so fast.

When the book won the Wattie three years later I took dad with me to the awards and loved watching people’s reactions when I introduced him to them. Dad had a long fulfilling life and was 95 when he died in 2010.

You have written that “the emotional amplitude of the book discomforted some stony Anglo-Saxon hearts”. Do you think, 50 years on, those hearts might be more receptive?

That phrase comes either from a letter written to me in 1973 from a university professor who wrote to congratulate me on the book or from The Times’ literary supplement review by Dan Davin, I can’t remember which.

It tells you more about the provincial European mentality of the 1970s, not just in New Zealand but throughout the world, to the public display of love and grief. If they read the book they probably held it at arm’s length from their breast.

But, after all, I was a Māori writer not a Pākehā one and wanted to ensure that Tangi was an emotional text as well as a written one and, actually, it’s better listened to – an oral text where the cadences and nuance come from the poetics and sung nature of waiata tangi (laments for the dead) and the drama enacted by the speaker.

Yes, those hearts are more receptive. We’re allowed to cry in public now.

Its emotional depth recommends it to anyone dealing with loss – have you had much feedback over the years about its ability to help people?

Yes, no matter the public occasion, people will always bring their dog-eared copies to sign, or sob on my shoulder, even when I travel internationally in my indigenous writer guise.

And there’s a heartfelt memory from an Amazon customer on the internet that I can quote: “Witi Ihimaera wrote this book for his father. I read it in 1975 and wept for my prick of a dad. I grieved for the love we never shared.”

So maybe there were some hearts back then when I wrote the book that weren’t so stony after all.

You’ve said that one of the challenges you faced was how to write a Māori novel in the English language. Did Tangi settle that question for you or has it been an ongoing project?

Following my Waituhi trilogy I realised that natural talent could get me only so far in destabilising the tendencies of the Western European novel and that the politics of being Māori [also] needed attention. I started to tell myself that writing was also a Treaty matter and the same requirements to ensure equity, equality and justice applied.

I came down to Dunedin as Burns Fellow to start the decolonisation process and placed an embargo on myself until 1986 when I published The Matriarch. So to answer your question, no, Tangi did not settle the question. In my aesthetics, my career is still one of seeking for the perfect sentence.

In my politics it continues to involve engaging Pākehā and, in particular Māori as represented within the New Zealand history by Pākehā, by rewriting those histories and reclaiming and rehabilitating Māori within them – a literary version of the Waitangi Tribunal process. It’s great to see my cousin Monty Vercoe and historians like Jacinta Ruru and others taking it to tribal level.

In your memoir Native Son, you said you looked to the Māori oral tradition – and the language – to meet the challenge of writing a Māori novel in English; waiata, kōrero, haka. Is the novel now part of that whakapapa?

What I meant was that when I wrote Tangi in 1970, the umbilical cord I used to try to get a different (Māori) aesthetic flowing through the book, was the singing nature of waiata, haka and kōrero. English was so flat and monotone and prevented the lift, buoyancy, lilt and spontaneity of Māori utterance.

Although Tangi has a lot of Māori aurality in it, it is, however, within a written tradition not an oral one. So, no, on balance, the novel is not part of the Māori oral tradition. It exists within the Māori written tradition – in English.

Tangi uses te reo Māori throughout, mainly translated – did you feel at the time there was a limit to how much te reo you could use, essential though it was? Has your approach to that question (if it arose) changed over the years?

At the time there was definitely a limit, made more difficult because I asked that we not have a glossary or that Māori words be italicised (I’ve just checked: there isn’t one and they aren’t.) As I’ve mentioned, the Eurocentric text predicated what was allowable and what wasn’t.

Nevertheless, I did try at the micro level as well as the macro level (Māori protagonist not sidekick, exclusively Māori setting with not a white person in sight) to destabilise the colonised text as much as I could within its limitations.

One battle I lost was the use of quotation marks for speech. I didn’t want any as Māori, I defended, “didn’t speak in speech marks”. I settled for the em dash, which was pretty fashion-forward, Janet Frame was using it.

In the 50th edition there are no speech indications of any kind.

There are many issues traversed in Tangi that remain as current as ever, including the younger age at which Māori die on average. You noted in your memoir Māori Boy, that in the 1950s a Māori man could expect to live to just 54. Was that inequity explicitly part of your novel’s purpose?

Oh my god, yes. My father Tom was symbolic of all that was good and precious in rural Māori culture, the culture of the kāinga (village), marae, whenua, awa (river) in all its dimensions.

In the book dad is all these things. When you overlay that primal story with the boy Tama’s, the novel balances itself on the fulcrum with the contemporary story of a culture being urbanised through the urban migration.

There’s a lot of loss happening in the book. But at the end, through the boy’s mother, there’s also the sense that there will be people to carry the culture on.

Similarly, Tangi could be written today in terms of its detailing of inadequate housing and issues of land ownership. Are there issues raised in Tangi that you might have thought would be in our past by now?

All these political issues you are referring to are implicit in the book rather than explicit. I was learning all the time as a young untried writer but one of the lessons from my mentor Noel Hilliard was to always leave spaces in the work so that the reader could enter and make what he, she or they wished of what was being written.

What needed to be addressed in your 50th anniversary revision of the novel?

The 1972 Tangi was a young writer’s book. The 50th anniversary 2023 version is the wiser, older writer who has, as Marcel Proust has written, passed a certain age when the child I was and the souls of the dead from whom I have sprung have truly lavished on me their riches and spells, their taonga (treasures) and wairua (spirit).

This has also helped me in my career as an international indigenous writer, walking the talk as I have continued doing this year. I’ve come a long way from that bed-sitting room in London.